Although learning sport is the acquisition of skills, most coaches have not studied the science of skill acquisition.

The typical coach profile: they grew up playing sport. (For our purposes here, let’s say tennis.) They took lots of lessons. Got good too. Played in college. Maybe played a little… maybe a lot of pro ball.

Somewhere along the line, if they still love tennis, and don’t want a “real” job, they start teaching the game.

Their “method”? The way they were taught. Hey… it worked for them, it’ll work for you.

In other words, their method is inherited. The proof of its effectiveness… anecdotal.

Having skills does not mean that one knows how they got them. Or that they can pass them on.

Flipping over to the customers side of the equation… their common profile: they believe that better players make better coaches. Meaning they would pay their max for a lesson from Fed or Serena. (Neither of whom have any teaching experience) Also, the common customer has a lot of experience with school type learning. (Being told what to do, and how to do it.)

In simple terms, they’re looking for a person who is… or was good… to tell them what to do and how to do it. Which is another way of saying that they haven’t dedicated any thought to what THEY want.

“If I asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” I’m pretty sure it was Henry Ford who said that.

And this explains why we’ve been giving the same tennis lesson for a hundred years. Probably.

Has a lesson in any sport ever been given that didn’t include the command to bend your knees? (My favorite worthless tip: watch the ball.)

In the last 100 years we have sliced bread, put a man on the moon, invented the internet… even cars that park themselves. Yet we still call on the same instructional methods that Bill Tilden wrote about in the 1920’s.

The trouble with teaching the game this way: it doesn’t really work. I mean… people do get better when they regularly take lessons. But that’s mostly due to the fact that they are regularly playing.

When you track regular lesson takers and people who play just as often but don’t take lessons… (I have), you are hard pressed to find differences big enough to justify the expense.

That’s a problem for those of us who want to give our students the value that they deserve.

Many will point to great players who were taught the way tennis has forever been taught, as proof of the methods effectiveness.

This is also anecdotal.

We’d have to clone people, run them through the various “methods”, and compare each clones results to definitively prove the claim. I’m pretty sure no one has done that… yet.

The truth is that everyone has been exposed to the information processing method of skills acquisition. If we dyed every kids hair blue, professional tennis would be dominated by blue haired people. (I stole that line from the great European football skills acquisitionist, Mark O’Sullivan)

It’s more likely that the good got good in spite of way they were taught.

*******

Two Camps

Skill acquisition has two main models.

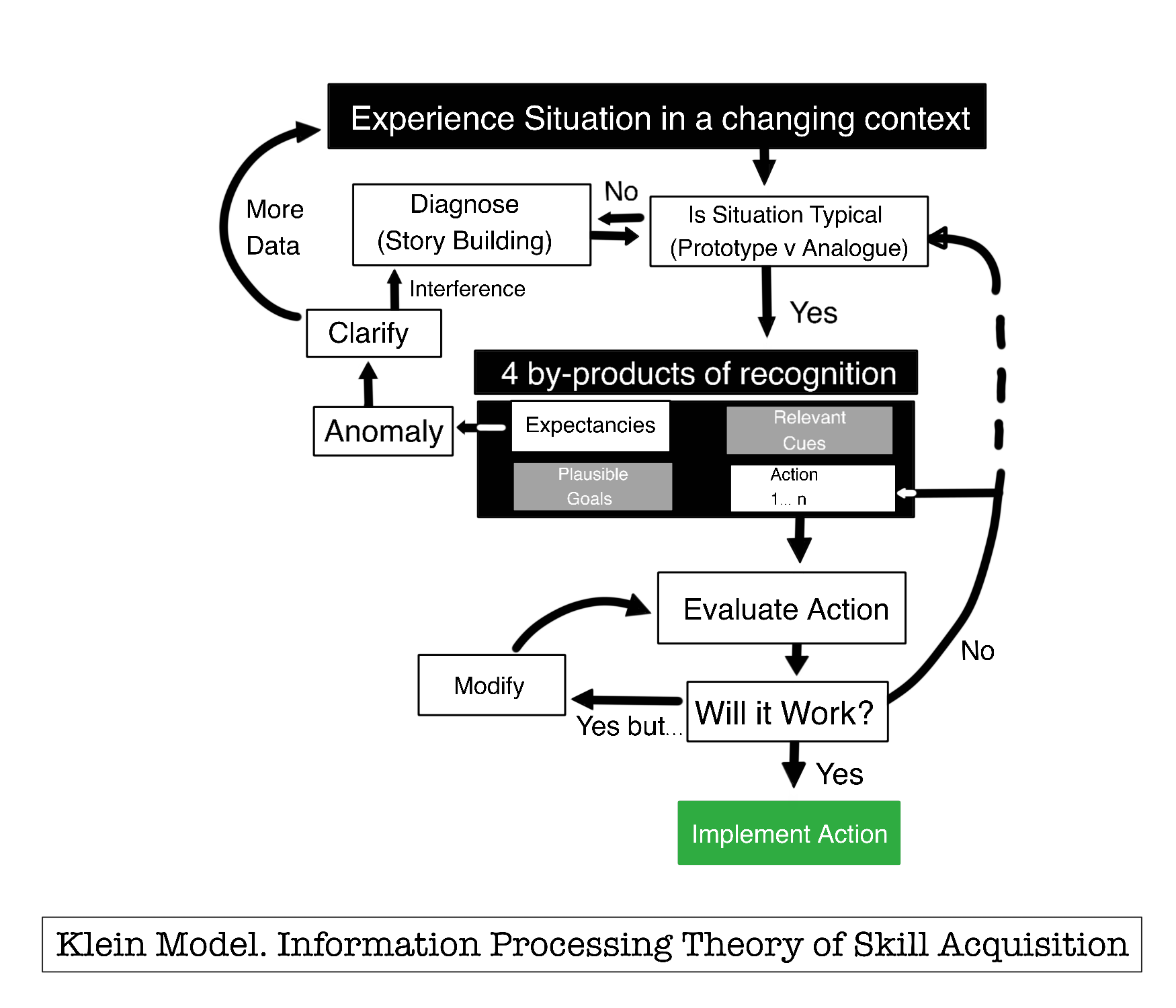

1) Information Processing. Skill is the recall of a program within us.

2) Ecological Dynamics. Skill exists in our relationship with a specific environment.

We all know the first. It has dominated sport for all of our lives.

In this camp learning is linear. It’s also outside-in.

The teacher is an oracle.

There are right and wrong ways.

The method is simple, and linear. A teacher explicitly prescribes “right ways” (model techniques, movements and strategies, aka fundamentals) The student memorizes them through repetition.

The students ability level is assessed via comparison to the “right ways”.

Of course there are deviations in the program. Some teachers drill less. Some are less strict with the fundamentals. Some teach more implicitly. Some have contrarian techniques.

But the bottom line is this: every method that has proper forms that are memorized through reps for recall at test time, is based on the Information Processing model of skill acquisition.

According to IP you are a fully autonomous system. Everything happens in your brain. Meaning skill is literally all in your head.

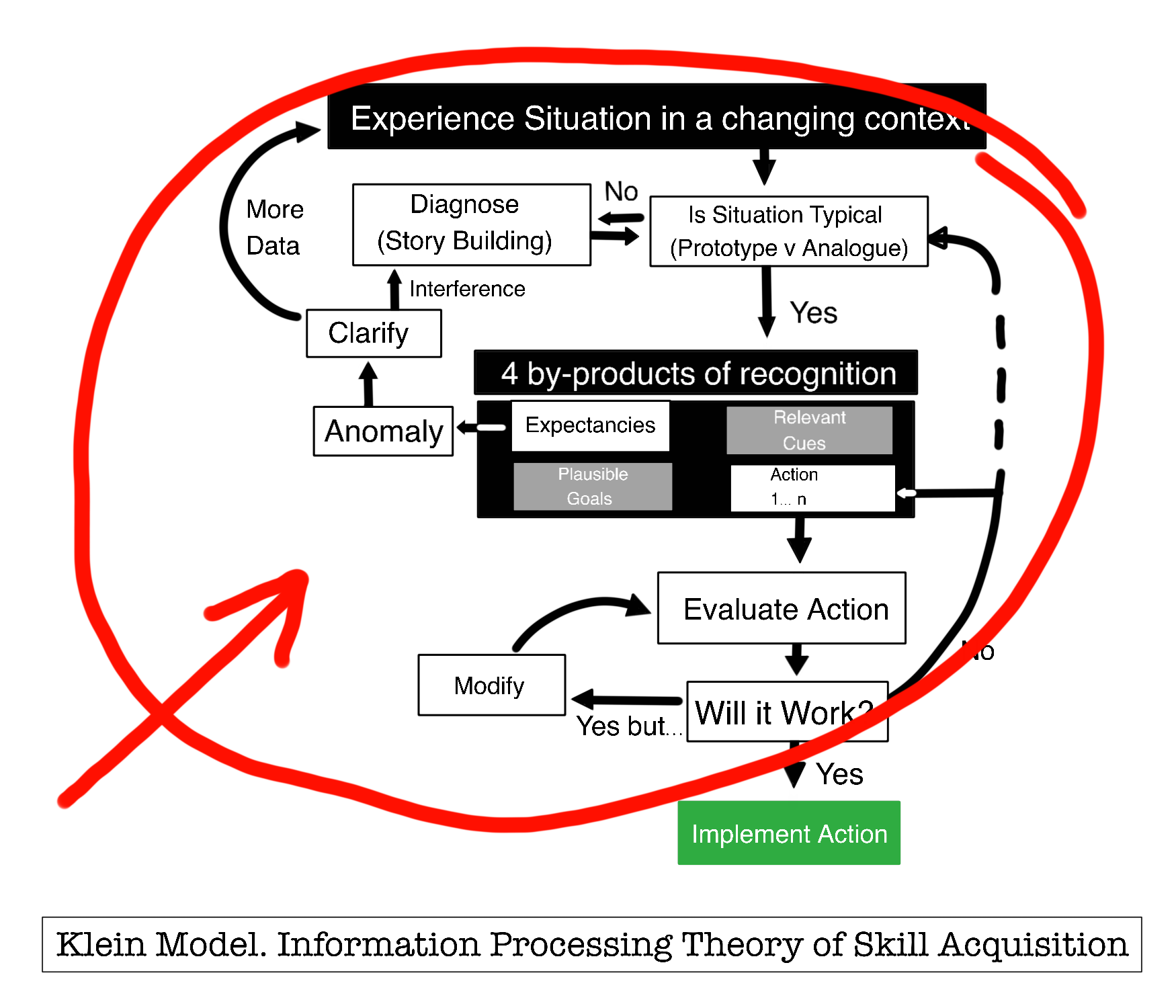

There are some significant problems with this model. But instead of getting bogged down in detail… (and boring you more than I already have), for now I’ll focus on the biggie.

All this detail…

… and then “Implement Action”. Without any explanation about how that action is implemented.

I can assure you that the implementing of the action is at least as complicated (probably more) than the choosing of the action. In fact, no one is really sure how we implement action. And that Truth is omitted from the model.

In other words, the IP model makes it seem like we understand more than we do.

My other BIG problem with IP is that it isn’t complete. A player can have the ability to perfectly execute the fundamentals… and still suck in match play. This is conveniently interpreted as a mental issue… or maybe a it’s general lack of ability. (Whatever that means.)

But whatever the root of the issue… it’s solution requires you to consult an “expert” in another field. Imagine repeatedly visiting a doctor only to have them finally confess that they can’t “fix you”.

IP is an engineering approach. An attempt to construct a reliable, predictable system. The thing is that reliable, predictable systems depend on reliable, predictable components.

People and sport have neither.

*******

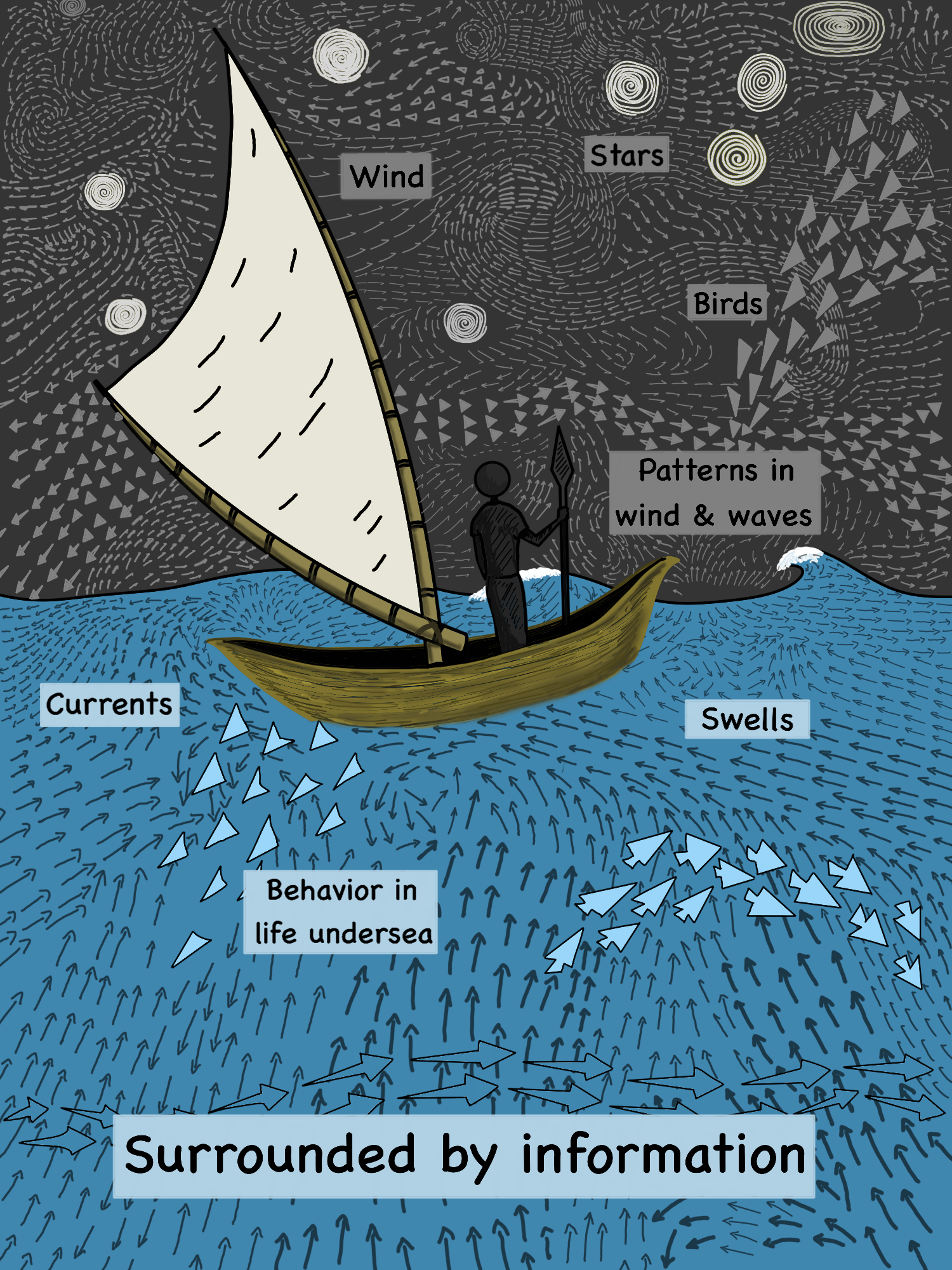

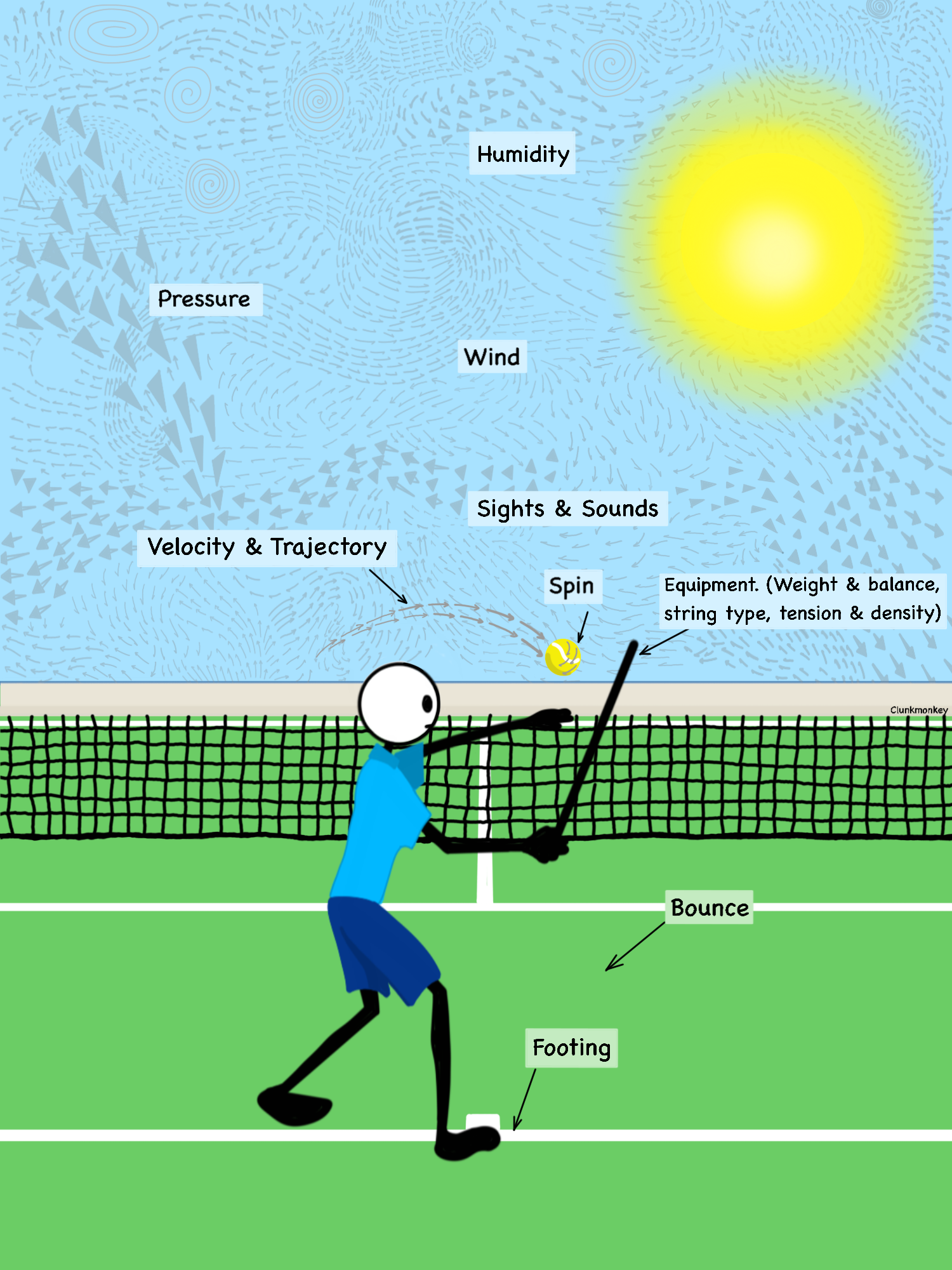

The second camp, Ecological dynamics, views skill as something that emerges through our relationship with a specific environment.

Think how a radio tunes into information in the surrounding environment and translates it into sound.

That’s us. Except sport is tuning into information and translating it into action.

A super simple example: you’re looking for a grocery store. Before leaving you checked a map, but now you’ve forgotten the route. And your phone has no service. You’re lost.

You see someone walking towards you carrying a bag of groceries with the logo of the store you’re looking for. An idea pops into your mind: ask grocery carrying person where the market is.

This was not your plan for finding the market. In fact, your plan for finding it failed. But… new information emerged. You tuned into it and figured out how to use it.

The great Carl Woods (a world-renown skills acq researcher) calls this “wayfinding”.

Our early ancestors pointed themselves in a direction that no one had traveled before. (At least no one that they knew) All was unknown. No one could show them the way.

(“WayFinding” credit: Carl Woods)

Our existence is proof they discovered their way.

Is it so hard to imagine that this happens in… everything?

Our brain processes 11 million-ish pieces of information… every second. We are only aware 30 to 40 bits of those millions.

Picking the key 30 or 40 pieces is the big trick. Compounding the issue… they can change from minute to minute. Further compounding the issue… they are unique to each of us.

Think of how a business person interprets a city. Now look at that same same city through the eyes of a parkour athlete. The buildings are transformed from opportunities for money making to opportunities for movement.

This is the ecological dynamics… or dynamical systems view of skill acq.

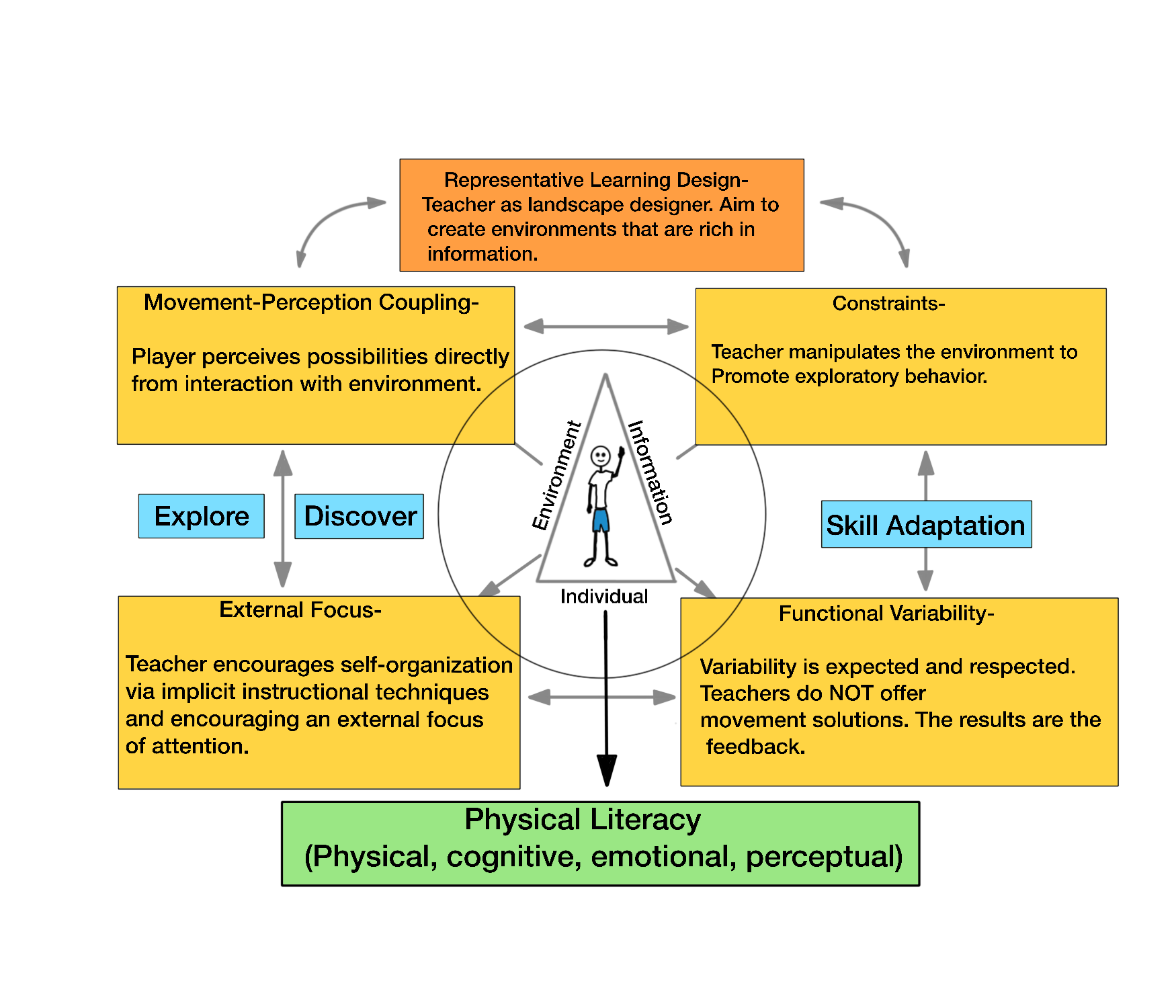

In this approach “learning” is developing your relationship with a specific environment.

Obviously, this perspective turns my profession on it’s ear.

Learning is non-linear.

The only “right” way is your way. And that has yet to be discovered. (Transforming a coach from oracle into guide.)

Also, students are assessed only against themselves.

There exists a broad belief that if you leave people to figure a thing out, they’ll figure it out “wrong”.

I’m pretty sure that’s marketing from the teachers lobby. Anyway, the research says otherwise.

For example, in this recent study comparing expert to novice fencers, it was seen that the novices focus mostly on the foil, while the experts focus mainly on the upper torso.

No one taught the beginners or the experts where to focus. They all started at the foil and “learned” that the upper torso gives better information by exploring the fencing environment.

Another thing about Ecological Dynamics: it’s complete. There is no need to look elsewhere (ie. Sports psychiatry) for explanations. Performance is rooted in the performers perception of their environment. When performance suffers, perception has been altered. (And vice versa)

Coaching from an Eco D perspective is like farming. A farmer can only do so much. They use experience to create the conditions that make a good crop possible. But they know that the outcome emerges from a complex system that is unpredictable and beyond their control.

Returning to the grocery store example… the IP approach would prescribe that the student memorize the way to the store. A good coach might also prescribe a plan B… just in case.

An Ecological Dynamics approach would have the student imagine how many ways they can get to that store. Explore each, and use the ones that work best for them.

I’ve been teaching this way for more than a decade. I can report to you that the dimensions of the understanding of a subject that’s approached from an Ecological Dynamics perspective are far greater than what is learned via IP.

*******

Perhaps Eco D still seems fringe to you?

Good! Advances come from the fringes. The mainstream has an obvious interest in maintaining the status quo.

But the list of studies showing the ecological dynamics approach results in superior transfer to information processing is long… and growing.

Globally, football (soccer) dwarfs our NFL and MLB (combined). It is the most thought about, most coached activity in the history of man. Ecological Dynamics is taking over football.

My prediction: in the next 10 years the tennis world will be wondering why we wasted so much time on the information processing model.

p.s If you found this interesting, I wrote a book that teaches tennis from an Ecological Dynamics framework. You can buy it here. I mean, please… please buy it here. (Does that come off as too needy?)