A friend sent me a video of a baseball coach explicitly instructing a major league infielder about how to catch.

The comments under the video:

“Great coaching!”

“Fundamentals, fundamentals, fundamentals.”

“How the Greats stay great.”

And blah, and blah, and more blah.

What I saw was a guy trying to teach a fish to swim… with shitty technique.

First off, the average major league fielding percentage is over 98%.

And second, the absolute last thing you want your first baseman thinking about, as the go ahead run barrels down the base path towards him, is if he’s catching the “right” way.

There is no ‘right’ way.

Fred wasn’t the first or last to make the observation.

Greetings and Salutations

If you don’t already know me… please allow me to introduce myself, I’m Tim.

I like to think of myself as a getter and doer of it.

Notice I said I like to think of myself that way…

After a stint as a starving professional tennis player I thought I’d check George Bernard Shaws theory about doers and teachers.

Thirty years… 40,000 coaching hours, and twenty-two countries later… I’m still at it.

I have spent those years honing my craft. Thinking. Researching. Building. Borrowing. Outright stealing whenever I can get away with it.

There is a difference between thirty years of experience… and repeating the same year thirty times. Taking the act on the road is another level. The game may not change much from place to place, but everything else does.

I’ve coached in first world cities and third world pueblos. In country clubs and under thatched palapas during tropical downpours. Worked with every level… the elites on down to the ham -n- eggers. And – I have no way of verifying this – but I’m pretty sure I’m one of the only people to have hit tennis balls at 5000 meters (16,400 ft) and at 90 meters (282 feet) below sea level.

I have only met one person with even remotely similar experience. Not saying there aren’t more… just that I haven’t met ‘em.

I’m writing this while under quarantine in Patagonia.

Coronavirus.

“May you live in interesting times.” I now understand that saying was extended more as a curse than a blessing.

Awhile ago some colleagues in Argentina asked me to write up my method and share it with them. Whereupon they would add what they’ve learned… we’d send it to other colleagues… they’d contribute… and so on.

Think of it as open source coaching. We share. We benefit. Our students benefit. Sport benefits.

I loved the idea but… we’re so busy doing. Who has the time to write?

Well… we all do now.

If you’re reading this we’d love your advice.

Imitation

It was around fifteen years ago that I had a stunningly depressing realization: despite my efforts and presumed “expertise”… my students either got a little better or a little worse at about the same rate as everyone else.

Oh sure, they knew all about grips, swing planes, contact zones, stances, spins, and timing steps. They even knew about the theory of spin competition… Wittgenstein’s ruler… and the Pareto principle. Even entropy.

They would slay any written test.

But they couldn’t play their way out of a wet paper bag.

The best take I’ve heard on what jolts us out of flow: micromanaging the unconscious.

Ummm… that’s essentially how we make a living.

A lot of thinking brought some tough questions to mind: how much do I know about what I do?

Not the tennis stuff… I’d been playing the game since I was a kid.

The teaching. What did I really know about teaching? I’d been to a few USPTA seminars. Learned some drills, how to keep the line moving, bookkeep, and maximize my hourly.

Simulated professionalism.

Do I teach this way because I know it works… or because it’s the way I was coached?

People are largely imitators. We do much of what we do because it’s the way it’s always been done, or was done to us, or because it’s what the people around us are doing.

But… we’re a little creative too. We always add our personal touch.

The result… lot of iteration… and little innovation.

For example, people have used bags for centuries.

Wheels too.

But it wasn’t until 1970 that someone put them together and invented a suitcase he could roll through an airport.

Think about it… for hundreds of years people iterated the bags form. They added straps, handles, zippers, compartments too.

But the system of carrying things around was not innovated upon until that wheel was added.

Strategies over opinions

When you view things as outcomes you form opinions.

When you view things as systems you form strategies.

Strategies are a better coaching tool than opinions.

I ask students to imagine their game as a system… a patchwork of interconnected elements, and give me the parts list.

“Oh… you mean like a pieces of a puzzle?”

“No, I specifically do NOT mean like pieces of a puzzle.”

Puzzles can only be assembled in one way.

I tell them to think legos.

These are usually the parts they give me.

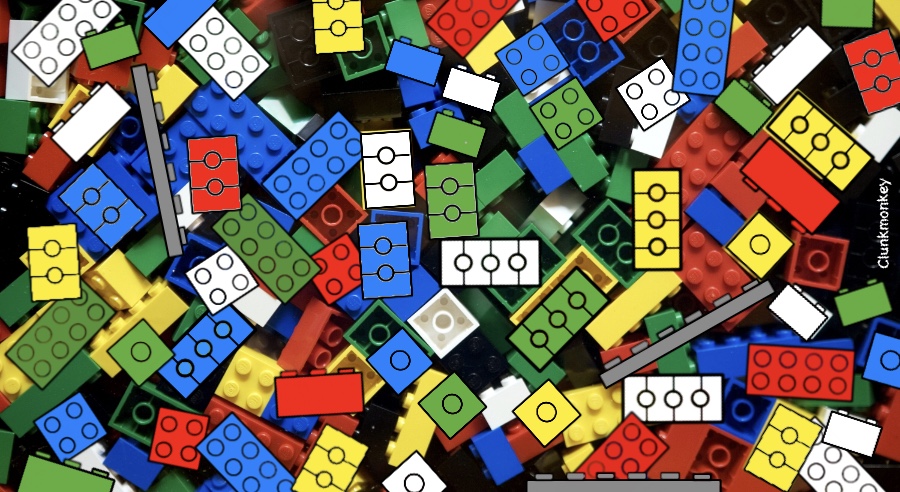

But the actual parts list looks more like this…

“What are all those other parts?”

“Well, you forgot to include the stuff you’re bringing to the table… like experience with other sports and sportsmanship and personal management and conflict resolution. You have some experience with psychology too. Don’t forget your beliefs about time, purpose, and possibility. Then there’s the wind, heat, cold, and sun. Dealing with disappointment, bad calls, bad bounces, and bad luck. Then there are good days, bad days, dog ate your homework days, sick days, super healthy days, tired days, and not ‘feeling well’ days. What do you do when you break a string in the middle of a point? How about when you’re sure the ball bounced twice but the other player says it didn’t? And when the player on the court next to you is having a complete meltdown? You even forgot to include the other player.”

So much time spent on technique. One lego in a thousand piece set.

No wonder my students weren’t thriving.

First Principles

I stripped my craft back down to bare wood and started again.

What do I know to be true about tennis? What could be true?

For starters, the player who hits the most balls in the court wins EVERY time.

We rarely talk about that… but it’s a fact.

What percentage of lessons do you think start by stating the simple point of our game: all you gotta do is put the the ball in the box?

Why do we spend so much time teaching people how to do it? Because we think people can’t figure how to do it on their own? That if they aren’t taught… they’ll learn wrong?

It doesn’t make sense. If there are right and wrong ways and our habit is learning the wrong ones… we wouldn’t have survived as a species.

Who benefits the most from that thought?

Coaches do.

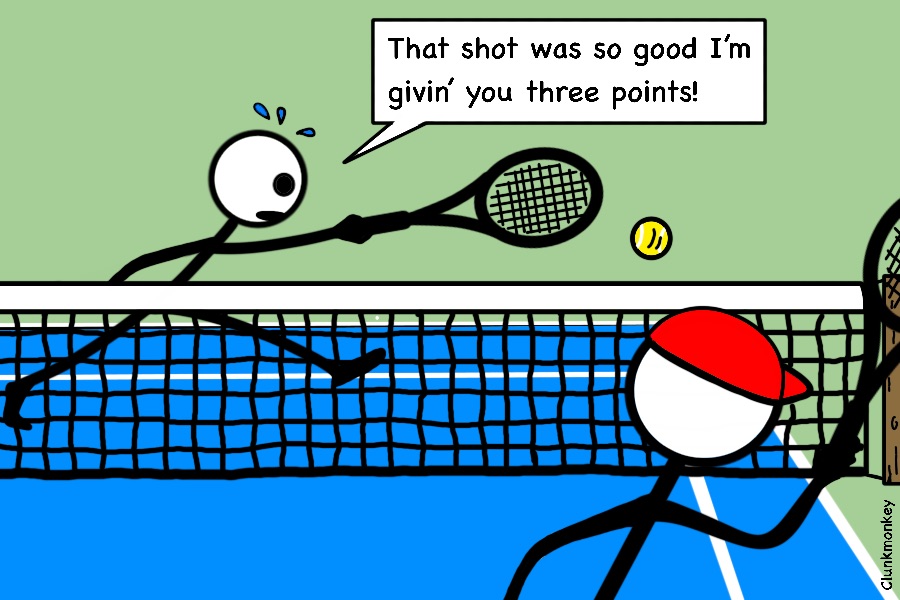

Another true thing: tennis doesn’t have extra point plays. No home runs. No 3 point shots. Every point… whether won by the greatest shot ever hit, a miss-hit let cord winner, or an error from the other player counts the same.

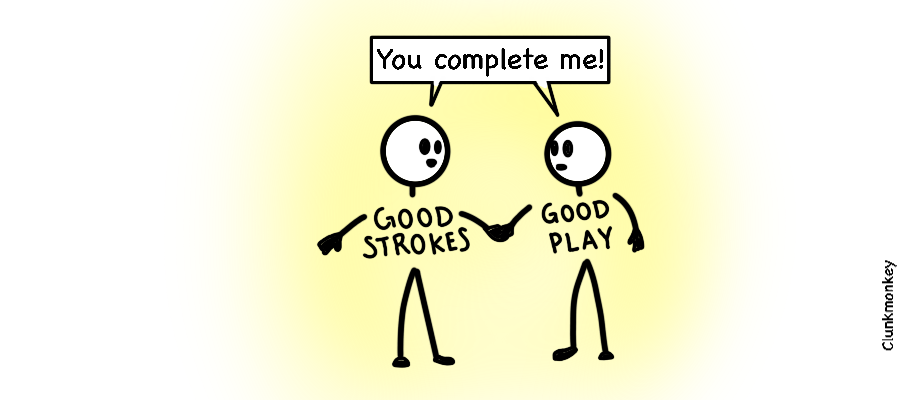

Could it be true that form matters too?

Since there are no judges and no style points, form would only matter if good strokes produce more consistency?

There is no objective evidence that they do.

I videotaped an assortment of strokes. Good. Bad. And the ones that keep you up at night. Highly decorated colleagues and I watched the tapes… pausing them at the moment of contact. Predicting the outcome was the game.

We couldn’t do it. Not reliably anyway.

This probably won’t surprise you but we consistently overestimated the better strokes and underestimated their ugly cousins.

Not exactly great science… I agree, but I haven’t been able to find any, so it’ll have to do for now.

There are exceptions to what I’m about to say but it’s directionally accurate: a players technique only roughly relates to their level of play.

If they don’t drown under the demands of 3.5 (4 UTR) play then they are one of tens of thousands of 3.5 players.

How they comport themself among those tens of thousands of 3.5 (4 UTR) players… that’s a story of skills, ideas, frameworks, and mental models.

The problem with intuition… it’s intuitive

But most can’t let go of this thought…

Our thoughts are not as reliable as we think they are.

We are the species who figured out a way to send some of our colleagues to another planet… and burned others for being witches. Shitty witches too. I mean… is a witch who can’t put out the fire even worth the match?

What? You think things are different now?

Twenty-four percent of Americans still think the sun goes around the earth. And the flat planet society is making a big comeback… especially in the NBA.

Intuition is easily misled… often confusing correlation with causation.

The other issue with intuition… it’s stubborn.

Here… I’ll show you:

You’re on a game show. Your host… Monte, presents three doors for you to choose from.

Two doors have a goat behind them, one has a new Ferrari… wait… that’s not very environmentally friendly, let’s change it. The winning door has a Tesla behind it… that’s better.

“Which door is the Tesla behind?” Monte asks.

You choose door #2.

Monte… your host, opens door #1.

Two doors left.

Monte asks if you’d like to trade the door you chose for door #3.

It’s 50-50 now you figure so… nah… no trade.

Monte double checks. “You sure?”

Yes.

He opens your door and…

No… sorry. You lose.

It’s not bad luck. Your intuition misled you.

When Monte offered you door #3 the odds weren’t 50-50. There was a 2/3 chance that the car was behind door #3.

This is where intuition digs in: a two-thirds chance with only two doors? Impossible!

Monte’s no dummie. He knows he can’t reliably pay the bills by flipping coins with his contestants. So he hired mathematicians to hijack his contestants intuition and use it against them.

Shrewd… don’t ya think?

Here’s how the math works: the only way staying with your first choice would have won is if you picked right when there were 3 doors to choose from.

There was only a 1 in 3 chance of that happening. A 2 in 3 chance you picked wrong.

Those odds didn’t change when Monte eliminated an option. There was still a 2 in 3 chance that your initial pick was wrong.

And still your intuition won’t accept the answer. It’s called the Monte Hall problem and here’s the link for you to look it up and see for yourself: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Hall_problem

Don’t feel bad, I know the answer and I still get it wrong.

Happily, we’re in good company, when the problem first appeared in writing… along with it’s solution, more than a thousand math PHD’s wrote in to wrongly complain that the solution was incorrect.

Remember that the next time someone tells you to “go with your gut”.

Getting it

The game is about putting the ball in the box.

The aesthetics crowd complains when I state it that way, but at the root of their argument is agreement. After all, putting the ball in the box is the supposed by product of the good form they spend so much time on.

In other words, consistency is the underlying purpose to every tennis tip ever given.

Even concepts like defense and neutral were created to make it easier to put the ball in play. And offense… just a sporty way of saying “I’m gonna try to make sure this is the last ball put in play.”

We coaches like to cloak this stuff in all kinds of important sounding military language like forcing, defending, attacking, and concluding skills. It sounds more serious that way.

Then we organize them into colorful coach Wooden style pyramids. That makes the game seem like it has some order to it… and can be planned.

The more intelligent the coach the better the jargon and more colorful pyramid. But anyone who has played this sport knows how unpredictable and unplannable it is.

Marketing by confusion. It sounds cool. Makes the game seem complicated… and positions the coach as an ‘expert’ who understands it.

That’s good for business.

But… zoom out. All it does is complicate keeping the ball in play.

If expertise were as important as we’ve been led to believe… wouldn’t the ‘experts’ agree more?

There is this old saying: if you can’t explain something simply… you don’t understand it yourself.

Try this for simple: if you don’t miss you can’t lose.

When I say that everyone – coaches and players alike – throws up their hands and yells “NO! You are wrong… wrong… WRONG! It is NOT that simple.

Yeah… it is. Granted, keeping the ball in play a far easier thing to say than do, but still… it’s true.

99% of the time the statement draws the following question: “so… what you’re sating is that I could beat (insert famous player here), simply by keeping the ball in play?”

Remember when your first grade teacher told you there were no dumb questions? They lied. Pro tip: any question that starts with “so what you’re saying” is going to be dumb.

“First off… the professional game is a totally different animal. That being said… if by some miracle you were to find yourself up against (insert famous player here), and if by some even greater miracle you were able to keep more balls in play than (insert famous player here)… then yeah.”

Most of the players we coach can’t imagine it being true because whenever we talk about the importance of consistency, the image that pops into their heads is of themselves running around the court… pooping balls into play like a six year old girl. And no six year old girl is gonna out rally (insert famous player here).

Please don’t misunderstand me, there’s nothing wrong with hitting the ball like a six year old girl… if you are a five, or a five and a half year old girl. But nobody else… not even a six year old girl, wants to play like that.

Let’s be honest here, the reason that image comes to their mind is this: if their life depended on them putting five balls in play in a row… that’s the only way they could do it.

This despite the fact they’ve invested all kinds of time and money into learning slice, and topspin, and timing steps, and power, and pronation. But that image in their head is proof that it all sits on a foundation of sand.

“I can’t do it,” they tell me. “I won’t do it.”

“Do what?”

“Play like a pusher.”

Have you ever noticed how the players who make us do things we don’t wanna do… like keep the ball in play, always get the worst nicknames?

It’s as if the other players have unconsciously banded together in an attempt to shame these players into styles of play that they can handle.

Whatever. I wasn’t trying to get them to play in any specific way.

“There’s no right way to play,” I remind them. “Play any way you want. I’m just making sure you understand the first principles of the game.”

Sometimes the latter changes the former. Sometimes not.

The great Mats Wilander told me a story about some exhibitions he played with Jim Courier.

Their games contrast nicely. Jims a blaster and Mats is a grinder. But Mats is at least a decade older so Jim usually wins.

They were booked for three match series somewhere. The first two were long matches that Jim won. In the final match Mats was too tired to grind. He went for his shots… and won.

They were walking back to the locker room. “You played well today!” Jim said. “You should go for your shots more… you’ll win more.”

To which Mats replied, “yeah that may be true but… I don’t like playing that way. And I care more about having fun than I do about winning.”

The art of awareness

Remember my students fifteen years earlier? The people who could explain everything and execute nothing?

The difference between an expert player and a beginner is not information. It’s awareness. The expert is more aware of what goes on in a swing, a point, and a match than a beginner.

Meaning our job is to enhance our students awareness. And bouncing information off of them for an hour… even super cool sounding information, does not do that.

Awareness comes from realistic experience. Therefore the best instructional methods are the ones that incorporate realistic experience.

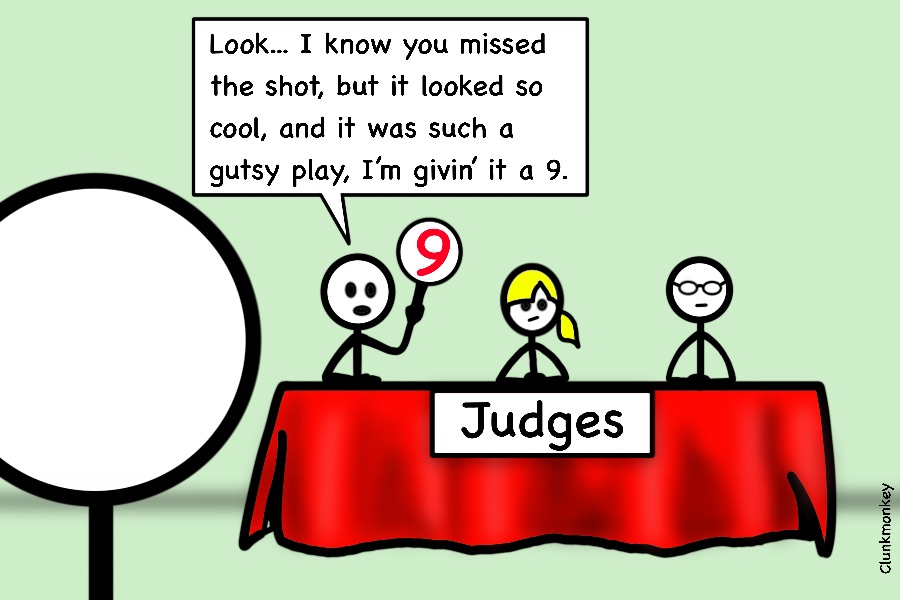

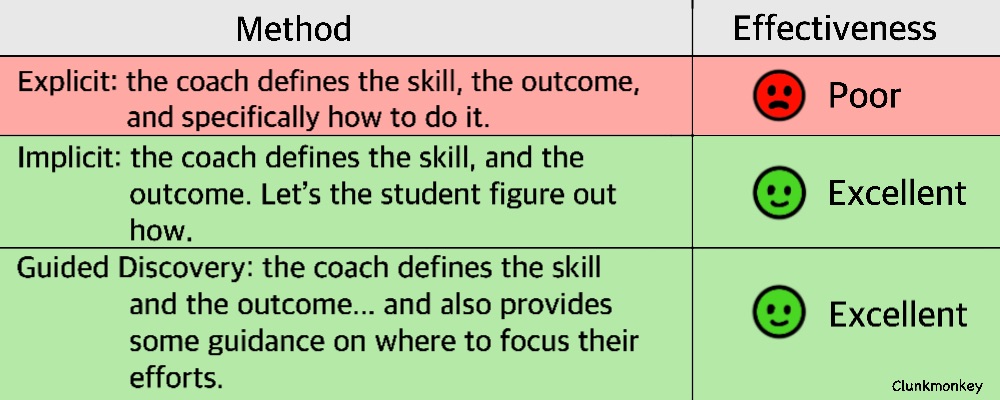

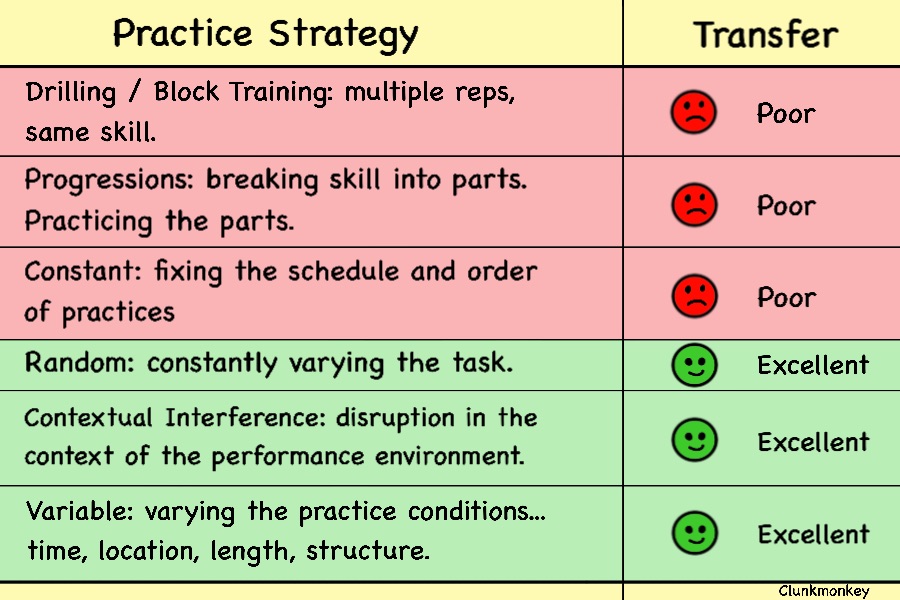

These are the most common instructional strategies along with their effectiveness ratings… according to research.

Explicit instruction is a sleeper. It appears to be effective because people can do what they are told to do in controlled settings.

But the world isn’t a controlled setting… and when they’re playing there is no one to provide exact instructions. Out here the fixes come undone like a paper kite in a tornado.

And it makes sense… why would any of us think that we can tell someone the best way to use their body? We know nothing about how it feels. We’ve never executed even the simplest of actions with it. And… maybe a more interesting question, why would any student believe us when we say we can?

Both implicit and guided discovery strategies result in deep awareness. That’s what we’re looking for.

There is some evidence that implicit learning is superior to guided discovery, but… it takes longer. And we all know how patient people aren’t.

I mainly rely on guided discovery.

This is where coaching becomes art.

We lead… but to their music.

I have taught with some super famous coaches… whose names I will not mention. They gave the same lesson ten times a day.

One of their players would run into some big wins – more likely in spite of their coaching than because of it – and the coach became a big deal. Suddenly they have a waiting list.

Not one of those students so patiently waiting for the tender ministrations of coach X, thinking to ask why the remaining 99% of his students aren’t doing as well.

Every student has a different tolerance for criticism, uncertainty, and failure. Success too.

“Why did you do that” a more productive question than “why didn’t you do this?”

We need to be able to read their subtle cues. Catch them before they crash. After is too late.

Fluency in strategies and methods is an absolute must. Flexibility too.

We may be leading. But they are the expert.

They do the digging. We place the “X”. “Can you think of another way to keep lots of balls in play? Is there a better place to wait for the ball? Another way to get that serve into my backhand? Another way to return a serve high to your backhand? Another way to get me to hit the ball where you want it?

Doing it

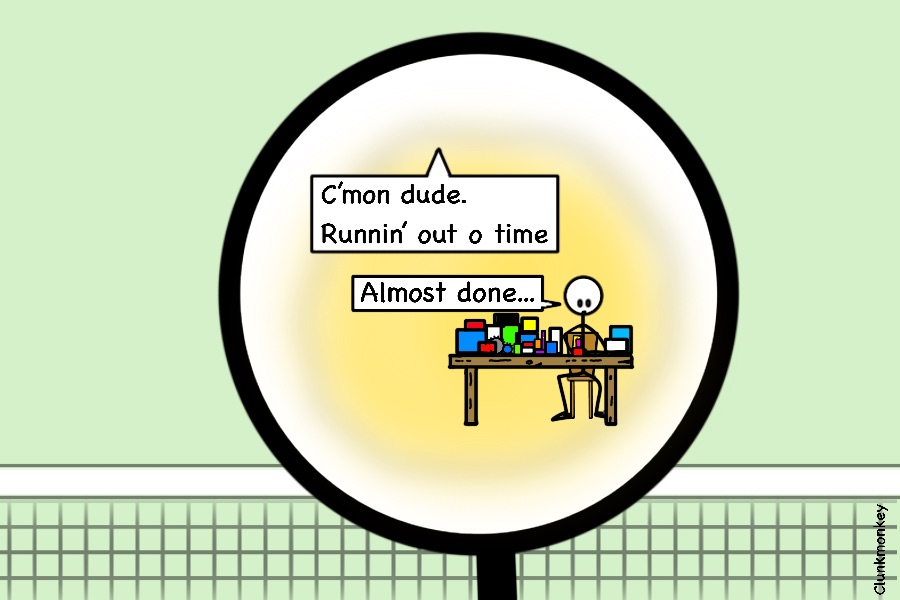

Meet Dick.

Watch Dick Drill.

Watch Dick fail.

We’ve all been a Dick.

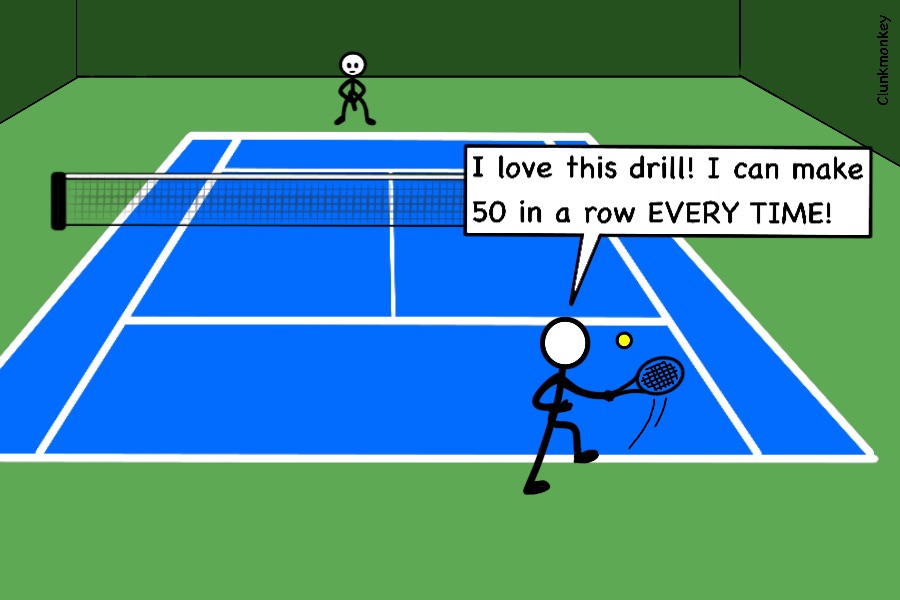

Perfect practice leads to perfect play.

We hear it all the time. It’s one of those sayings that sounds like it means something… until you try to figure out what the fuck it means.

What in the hell is perfect practice?

If the objective is to perform better… and by better I mean access the skills in match play that you can so easily get ahold of in practice, then perfect practice would be anything that brings that about.

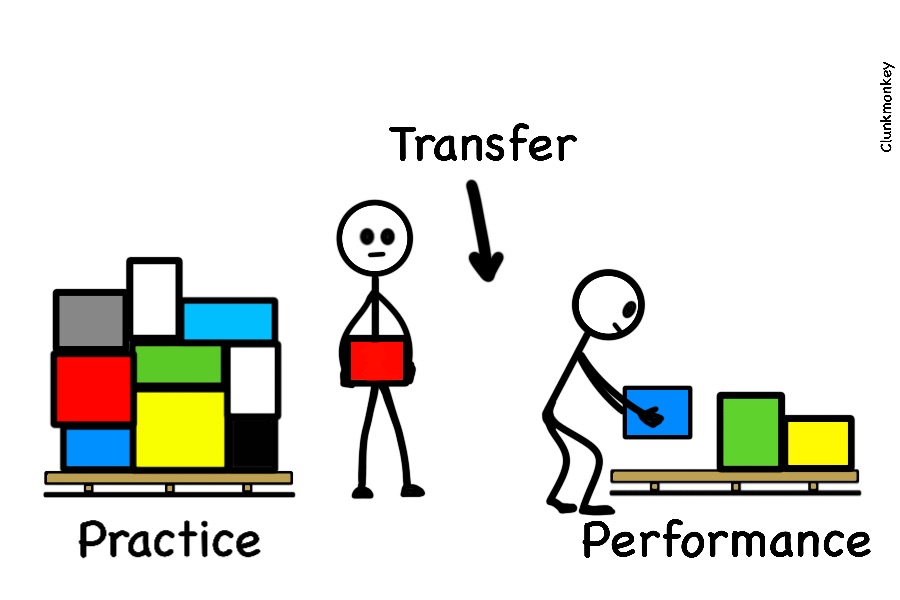

The key measurement of the effectiveness of practice is called “transfer”. Does what you practice transfer to your performance?

Here’s a research driven scorecard on the transfer of the most common practice strategies:

Drilling, progressions… cones, footwork ladders, people waiting in straight lines. Despite their poor transfer, these are the most popular strategies worldwide.

Why?

The simplest answer: there is some confusion over what exactly is being learned.

Before we do anything our brain cobbles together a mental model of what we are going to do.

Think for a moment of the incredible number of variables that model calls upon. Observations, ball speed, foot speed, heat, wind, spin, surface, bounce, movement, mood, energy, beliefs… the list continues.

We have maybe half a second to do it.

Keeping models available consumes resources and the brain guards those closely. Unless you know that the shot is going to immediately repeated, that model is trashed directly after use.

Think about the number of models required to play a point. Serve, return, possible forehand, possible backhand, deep balls, short balls, high balls, low balls, miss-hits, bad bounces, top-spin, slice, let cords… so many models to build, and discard, and build, and discard, and build… you get it… it’s tough work.

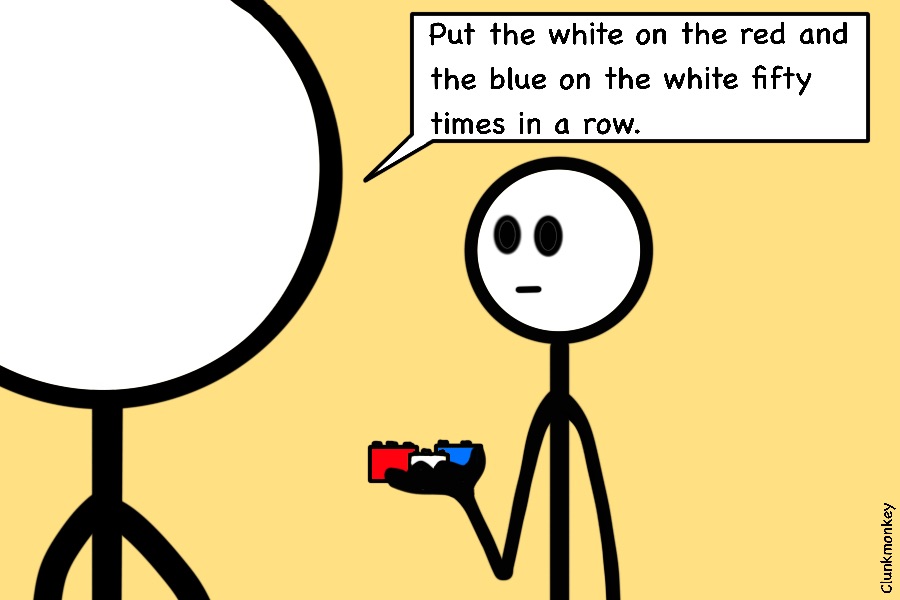

Now think about a drill. Hitting serves from a hopper for example. One model.

That’s easy.

Hitting cross-courts. A couple of models.

Remember… when your brain knows whats next it can keep the model up for use.

That’s why it feels like you’re getting better when you drill. When you can keep the same model up for use it frees up those resources normally consumed by building… and you can focus solely on making each rep better. Which is pretty easy to do. And feels great.

But you are NOT getting better!

Go deeper. The first principle of practice isn’t to improve a stroke. It’s learning to build better models faster. When you repeat the same skill over and over you are not building models.

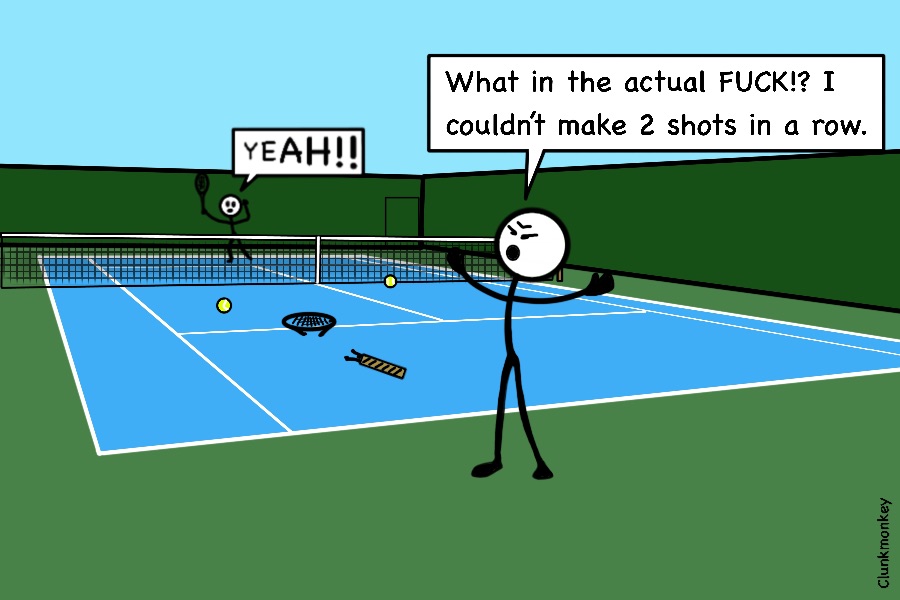

In other words… this doesn’t work.

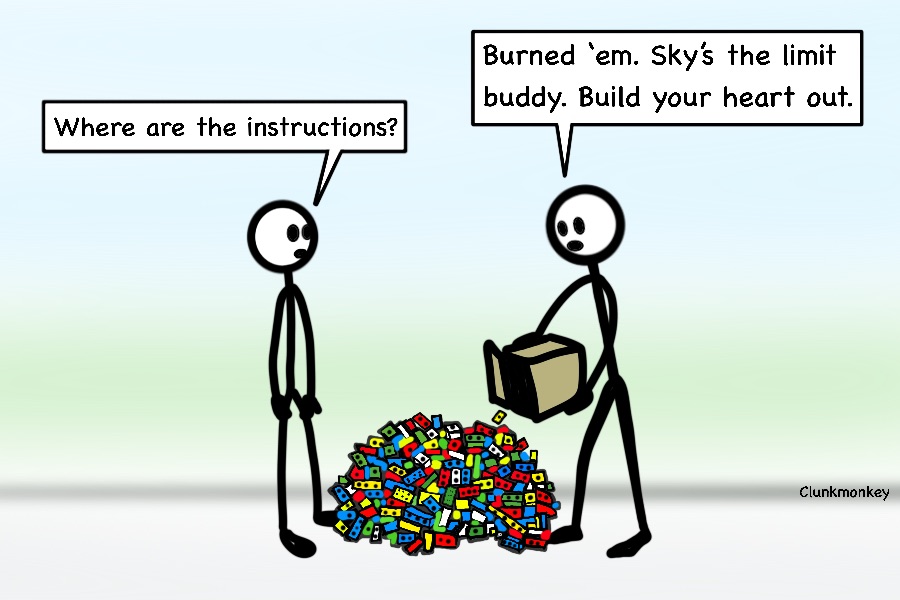

And this does.

It just doesn’t feel like it works.

And that brings up an interesting question that we should all know the answer to: what does improvement feel like?

In the 1990’s a group of researchers conducted a study on a college baseball team entitled “Contextual Interference Effects With Skilled Baseball Players“

They divided the team into three groups.

Two of those groups received two extra batting practice sessions weekly. The third group received no extra training.

The extra sessions consisted of 45 pitches. 15 curve balls. 15 breaking balls. 15 fast balls.

One of the groups getting extra BP was told what was coming and given all 15 in succession.

The other group got their pitches randomly.

The study went on for six weeks.

At the end of each week the players were asked if they felt that they were improving. The guys who knew what was coming said they were for sure.

But the randomly trained players… the guys who never knew what pitch was coming, they were sure they were getting worse.

At the end of the study the numbers came in. Group three, the control, improved 8%. Group one, the block trained group, improved by 26%. And group three, the group that was sure they were getting worse… improved by 57 percent.

The bottom line: context. The more closely practice replicates what is being trained for… the greater the transfer.

The game teaches itself.

Drills were created to maximize touches per hour. As we’ve discussed, the typical quiver of tennis drills is so far out of context that the transfer is abysmal.

Switch to “grills”… game based drills. (copywrite credits to coach John Kessel head of USA Volleyball) Eliminate the rest time in between points. Play serves that land out. Anything that increases realistic… in context reps per span of time on court will work.

And when your players whine and complain and swear to you that you’re making them worse… smile, now you know it’s working.

One more big influence on transfer: the learning environment.

Our students have been trained to be terrified of failure. Mistakes cost jobs and first choice colleges.

They’ll do anything to avoid that stuff.

But experimenting… taking chances and failing, is learnings love language. An expert is simply someone who has made every mistake in their field. That’s what Niels Bohr thinks anyway… and I agree.

Meaning our job is to turn this:

Into this:

Reframing failure is no easy task. It takes time… and technique.

I start by reminding students that whatever standards they hold themselves to off the court won’t work on it. “You May be a fully grown adult know it all at work, but here you’re a toddler… try to keep your fingers out of the sockets.

Failures need to be celebrated as another step towards excellence. At least that’s the way it’s supposed to work. If you catch them doing the same dumb thing twenty times in a row, switch to the avoiding repeated stupidity strategy. That one works too.

Winning

I always meet with people before I agree to coach them.

This is where we decide who will have what skin in the game.

My first question is what they want.

They always want to get better.

Makes sense. Until I ask them to define better… and they can’t.

Oh sure… they say stuff… like, “I wanna serve better… or hit the ball better,” but that’s where we started.

I drill down and… it’s usually wins they’re after.

People think winning will make the game more fun.

It’s not entirely their fault, sport has been marketed that way.

It’s not true. Winning does not make the game more fun.

In fact, I once met a researcher who was studying if being good at something made that thing more fun. His conclusion: yes it does… but only to the intermediate level.

It makes sense. We all know that it’s no fun to suck… or at least I do. But getting good… really good… well, the elites are always the most neurotic.

If better equaled more happiness, the pros would be fucking ecstatic. Watch them play. Does it look like they are having the time of their lives to you?

Just once I’d love to see a player in any sport give the following interview after getting their ass kicked? “Yeah… I got a natural ass whuppin’ out there but… wow, what a day! Today I got to play one of the best players in the word… and I got paid for it! This was a GREAT day!”

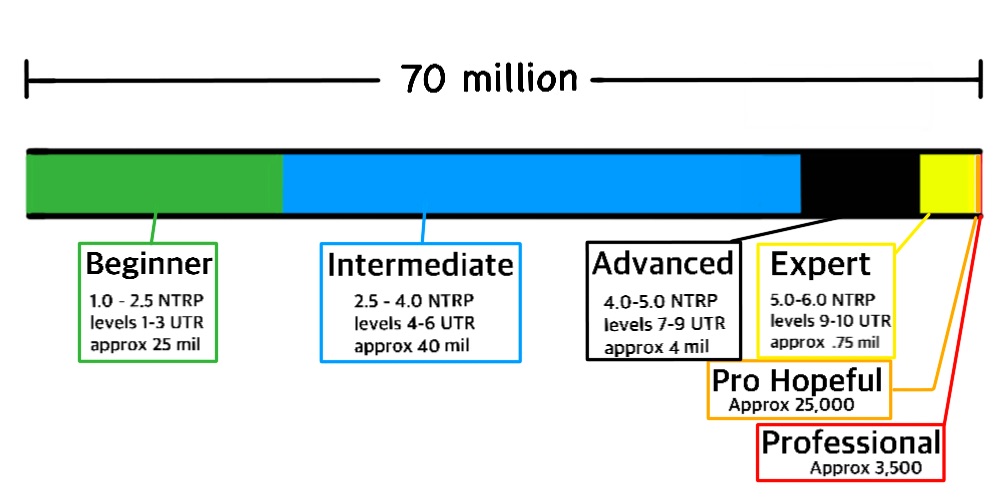

There are around 70 million tennis players on our tiny blue dot.

Here is roughly what that looks like.

Winning matters for those few thousand professionals and prop hopefuls. And if you have any experience coaching them… you know it’s a totally different dance.

But winning is irrelevant for the remaining 99.9995 % of earths tennis players.

Whenever a student tells me that winning is what they’re all about, I tell them to grab some poor sap they are ten times better than… drag ‘em onto the court, and beat the living shit out of them.

“No! Not like that. I want to beat good players.”

Then you’re not only about winning.

And that’s a good thing because worrying about winning eliminates the fun of play.

Actually it goes a little deeper. When an end result is the goal of an activity, the thing that separates you from your goal is the activity itself.

In other words, playing to win is playing against play.

Maybe you’ve heard of Torben Ulrich?

Torben was leading the number one seed, the great John Newcombe two sets to love in a long forgotten US Open match. A butterfly landed on the court in front of him. He paused so it could exit unscathed. And then lost the next three sets.

The press afterwards: did the butterfly break your concentration?

Torben: was I a butterfly dreaming I was a man, or a man dreaming I was a butterfly?

That one sentence tells you everything you need to know about Torben. Incredible guy! Super interesting. An accomplished musician… poet… artist. He was also one of the worlds top tennis players in the 1960’s and 70’s. The oldest player to ever play a Davis Cup match.

For years I heard rumored of an even wilder story about Torben. One of those stories that sounded so crazy people would lower their voices when they shared it for fear that others might overhear and entangle the teller in the unbelievable tale.

“Pssst… Torben once played a match with another pro that lasted for hours… without balls.”

“That’s not possible!”

Impossible except… it happened. Two great players went to a park and played a match without balls.

Finally I met the man. You cannot imagine a kinder person. There are no handshakes with Torben… it’s all hugs.

When I asked him how they worked it out he just shrugged and said, “when we got tired we ended the point.” Thinking about how they did it takes you out of thinking. Like… imagining what’s outside of the universe.

The cooperation… exercise… fun… and camaraderie… it’s one of the most original things I’ve ever heard of. Just writing about it makes me happy.

And as crazy as that story sounds, the truth is… when you finally penetrate the noise in peoples heads you find – often at the same time they do – that people are playing for similar non-competitive reasons… they enjoy the comaraderie, exercise, fun, the way it feels, or the honesty of doing something with no ulterior motives. They just didn’t know they could ask for that stuff.

First and foremost we are ambassadors for our sport. Our job is to make the game more fun for players of EVERY ability.

Never ever ever ever give up

Zoomed all the way out, tennis is a metaphor for life.

If there are points left to play… everything is still possible, no matter the score.

Can you play it that way? Can you play to the end with the same sense of possibility that you began with?

So few do.

People get distracted. They’re too far behind. Not playing well enough.

Then the excuses: not my day, the wind, the other players cheating, my shoes are giving me a blister.

Negativity, in the words of my great friend and mentor Jim Triolo, is 100% effective.

They ease off of the accelerator. Rarely in a blatantly obvious way. Usually they roll into a super high risk strategy.

You know the ole… “I’m goin’ down swingin’.”

I ask them why they’re quitting.

“I’m not quitting!”

“Of course you are. If you thought you could achieve your objective with this strategy you would have started with it.”

Too far behind doesn’t exist in tennis.

It doesn’t exist in life either. If you’re breathing… it’s all still possible.

Can you live life to the end with the same sense of possibility you began with?

Sure, statistics can be useful. But they can also be an excuse. Rely on them at your own peril… they only peripherally apply to an individual.

Rick Hoyt was born a quadriplegic with cerebral palsy.

The “experts” looked into his eyes and said no one was home. “Send him away,” was their advice. “99.9% of these people never launch.”

His dad didn’t give up.

School had no place for Rick. “He needs to be in an institution.”

His dad didn’t give up.

As a teen Rick saw a poster for a 5 mile run… he wanted to do it. But he couldn’t even stand… let alone run.

His dad… well, you know..

That was over 1000 races ago. Including 34 Boston marathons. 6 Ironmans. And a run across America.

Whenever I get in my own way – which is often – I think about team Hoyt.

Those are the best runners on earth… going out of their way to give respect to two people who inspire them.

Nobody… not even Rick and Dick I bet, would have dared to dream this shit could happen thirty years ago. And yet… there it is.

Please… reflect on that beautiful image for a moment.

This is why you must never ever ever give up.

Borrowing the words of a great coach… Fred Shoemaker, our job is not about new ways of doing… it’s about new ways of being.

Difficult things take time. Impossible things… a little longer.